The Biological Wonders of Breathing Forest Air

12/2/202510 min read

The Ancient Chemistry of Forest Air: How Phytoncides Affect Human Health

By David & Lovee Miller

Somewhat Curious

When you step into a forest of pines, firs, or cedars, the air feels different. You might notice a pleasant aroma, a sense of clarity, or even a relaxing drop in tension. We are curious about what, why, and how!

This "forest effect" isn’t just poetic imagery. It’s tied to a family of natural chemicals that trees release called phytoncides. Though the word itself wasn’t coined until the 20th century, humans have recognized the value of fragrant tree resins for thousands of years. One of the oldest written references appears in an unexpected place: Genesis 2:12, which mentions a region rich in "gold, aromatic resin, and precious stones." Connecting this ancient observation with scientific discovery, modern analyses of ancient resin samples have demonstrated that they contain molecular components—specifically, terpenes such as alpha-pinene and limonene—that are closely related to the phytoncides found in contemporary forests. (Ancient Humans & Terpenes: A Historical Connection, 2018) To further support this connection, various studies have shown how terpenes, extracted from ancient resins, share structural properties with modern phytoncides, revealing a chemical lineage that enhances our understanding of these natural compounds. (Piva et al., 2019) Although more large-scale studies are needed to fully solidify this link, current research already provides a robust foundation. This parallel suggests that the beneficial properties humans once appreciated in aromatic resins are now understood scientifically through the study of phytoncides. (Seasonal emission patterns of airborne phytoncides in temperate forests, especially in warmer humid seasons: A case study of Xishui National Forest Park, 2025)

This article uses that ancient line to show early peoples realized trees produce potent, health-affecting substances long before modern chemistry explained them.

Before proceeding, let’s frame our exploration with this guiding question: Can breathing forest air measurably change our biology? With that in mind, we’ll now look more closely at what phytoncides are, how they impact the human body, and why “forest bathing” has become both a wellness trend and a field of scientific inquiry.

What Exactly Are Phytoncides?

Phytoncides are volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which means they are chemicals that easily become vapors or gases. Trees and plants emit these as part of their defense system. The name comes from Greek roots: "phyton" means "plant," and "-cide" means "to kill."

Plants aren’t trying to hurt us; they’re protecting themselves from bacteria, fungi, molds, and insects. The fact that humans benefit from these chemicals is a biological bonus.

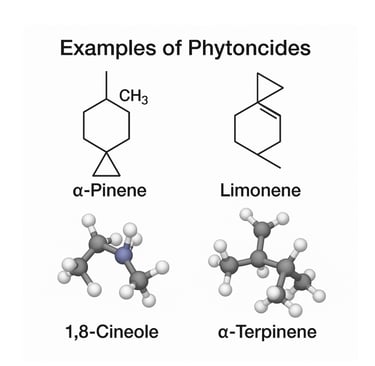

The Chemistry Behind the Scent

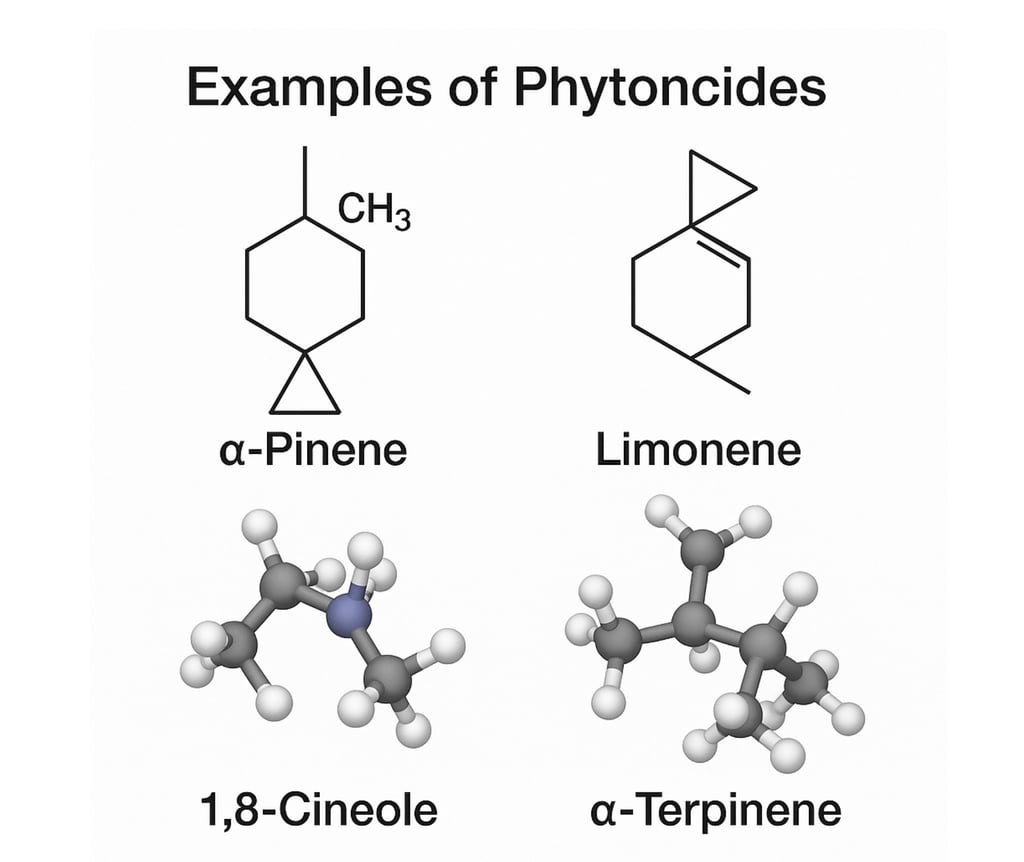

The majority of phytoncides belong to the chemical class known as terpenes and terpenoids—chemicals made of smaller units. These units are called isoprene units, each containing five carbon atoms. (PHYTOCHEMISTRY AND PHARMACOGNOSY – Plant Terpenes, n.d.) Imagine these molecules as Lego blocks that build plant fragrances. When two isoprene units join, they create a larger structure called a monoterpene; an example is α-pinene. These simple connections give rise to intricate aromatic structures that yield the varied scents of forest air.

The most common forest phytoncides include:

α-pinene

β-pinene

Limonene

Camphene

Bornyl acetate

Eucalyptol (1,8-cineole)

Why this structure matters

These molecules share several traits that make them powerful:

1. Small and volatile, with boiling points as low as 155 degrees Fahrenheit for alpha-pinene, these compounds easily evaporate into the air we breathe. (80-56-8 CAS MSDS (alpha-Pinene), n.d.)

2. Lipid-soluble — they dissolve in fats and oils, which allows them to pass through cell membranes and enter the bloodstream.

3. Reactive — their structures allow them to interact with microbial cell walls, giving them natural antimicrobial properties. (Phytoncide, n.d.) (Phytoncide, n.d.)

4. Aromatic — they can easily attach to olfactory (smell) receptors in our noses, which helps them influence emotional and autonomic brain centers. (Essential Oils, Phytoncides, Aromachology, and Aromatherapy—A Review, 2023) (Thangaleela et al., 2022)

In other words, phytoncides float, diffuse, enter, and affect—a perfect recipe for influencing human biology.

How Humans Absorb Phytoncides

When you inhale forest air:

1. Phytoncides enter the nasal cavity.

2. They bind to receptors and stimulate the olfactory bulb, which connects directly to the limbic system—the emotional, memory, and autonomic center of the brain.

3. Some molecules can cross the thin walls of the lungs and enter the bloodstream, which carries blood throughout the body.

4. From there, they interact with immune cells and stress-regulation pathways.

No supplements or devices, just breathing. These natural entities underpin immune and stress effects discussed next. For those seeking practical steps to benefit from phytoncides, spending at least 2 hours in a forest environment two to three times a month could significantly enhance your well-being. Regular exposure like this is optimal for harnessing the immune-boosting and stress-reducing properties of forest air. (Breathe Deep: How Forests and Phytoncides Boost Your Health, 2025)

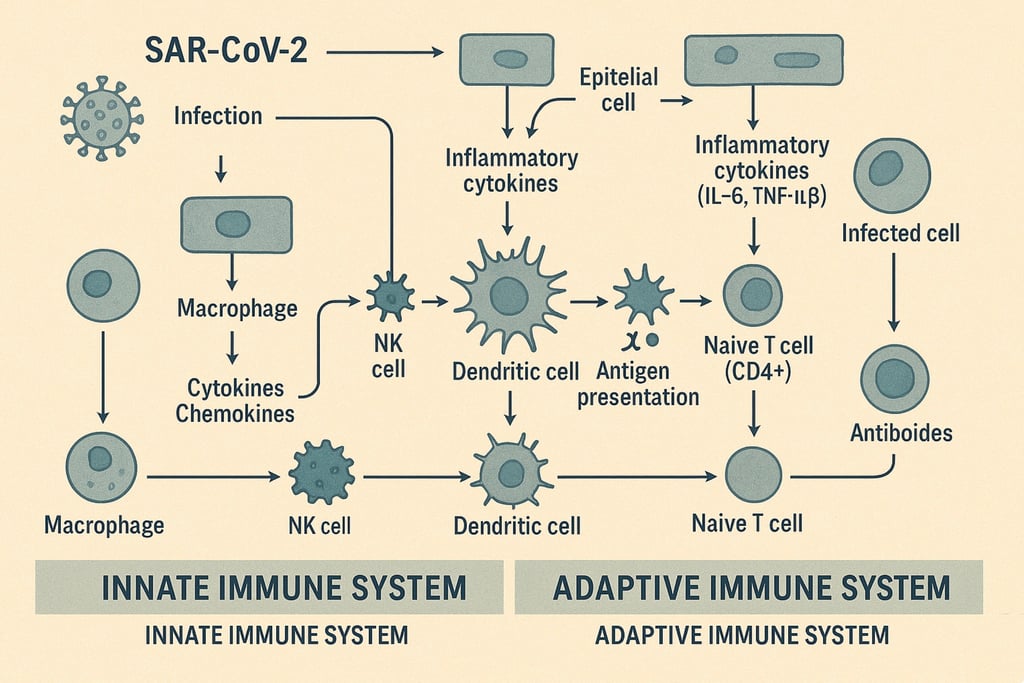

How the Human Immune System Works (A Brief Overview)

To understand how phytoncides influence immunity, it helps to review the basics. This is all too familiar, since we all became (more realistically, forced to become) immunology experts when COVID hit the scene.

The immune system has two major arms:

1. Innate Immunity (Fast, non-specific)

First responders

Includes natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and neutrophils

Acts within minutes to hours

2. Adaptive Immunity (Slow, targeted)

T cells, B cells, antibodies

Learns specific pathogens

Provides long-term memory (e.g., after vaccines, remember COVID?!)

Forest phytoncides primarily interact with the innate immune system, particularly NK cells (which target and destroy virus-infected cells, cancer cells, and help during bouts of seasonal colds). (Li et al., 2006)

How Phytoncides Activate Natural Killer (NK) Cells

NK cells circulate constantly, scanning for:

Viruses

Bacteria

Tumor cells

Damaged cells

They eliminate threats by releasing:

Perforin (drills holes into the target cell membrane)

Granzyme A/B (enzymes that trigger cell death)

Granulysin (antimicrobial action)

Forest Exposure Increases NK Activity

Multiple studies, primarily from Japan’s forest-medicine research groups, show a 40-50% increase in NK cell activity after a 2-hour forest walk. (Li & Q., 2007) These studies often employ randomized controlled trials to ensure the validity and reliability of the results. In such trials, participants are randomly assigned to either the forest exposure group or a control group that experiences an urban environment, allowing researchers to isolate the effects of forest exposure. To put this in perspective, typical daily fluctuations in NK cell activity can range from 10% to 20%, depending on individual health and lifestyle factors. Thus, the forest-induced boost represents a significant change beyond these natural variations.

Elevated levels lasting up to 7 days

After a 2–3 day forest trip, elevated NK activity can persist up to 30 days (Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011)

Phytoncides appear to:

Increase NK cell count

Enhance NK cytotoxicity

Boost expression of perforin and granzymes

Reduce stress hormones that inhibit immune function (Li et al., 2006).

Cortisol Reduction and Nervous System Effects

The autonomic nervous system has two modes:

Sympathetic (fight-or-flight) increases the release of cortisol and catecholamines, which increases "stress" and inflammation

Parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) reduces both stress and inflammation

Phytoncides—like α-pinene and bornyl acetate—tend to:

Lower sympathetic tone

Increase parasympathetic tone

Reduce cortisol (the stress hormone) by 10–16%

Improve heart-rate variability (HRV), which is a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat and is a marker of how well the body can respond to stress (Effects of olfactory stimulation by α-pinene on autonomic nervous activity, Ikei et al., 2016)

The feeling of calm that people describe in forests has a measurable biological footprint. It is real.

While the case for phytoncides is compelling, it’s also important to consider the skeptical perspective and scientific limitations.

A responsible article should acknowledge limitations. Here are the main skeptical points. Small sample sizes: Many forest-medicine studies use 10–20 participants. Multiple variables at once: Is it the phytoncides, the forest silence, the absence of cars, the greenery, lower temperatures, lower pollution, fresh air, sunshine, the unknown zillion of other molecules floating around in forest air, or the exercise of the hike you took to get there? Likely, a combination of all the above. To isolate the effects of phytoncides from these variables, researchers often use controlled environments or compare forest exposure with urban settings to account for extraneous factors. These experimental designs, including random assignments and controlled settings, aim to create conditions where the role of phytoncides can be more clearly understood.

NK cell increases may not always translate into long-term clinical outcomes: We don’t yet have large-scale studies linking forest exposure to lower cancer incidence or long-term disease prevention.

Diffuser oils are not equivalent to the whole forest experience: Essential oils mimic some terpenes, but real forests release hundreds of interacting compounds.

These limitations open avenues for further research. Among them, the impact of forest environments on long-term health outcomes is ripe for future study. Researchers could focus on establishing a stronger causal link between forest exposure and sustained improvements in health markers to guide evidence-based practices.

All that said, the data consistently show: lower cortisol levels, improved mood, better blood pressure, and increased NK activity. No single mechanism explains it all, but the effects are real enough to warrant attention.

A Brief History of Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku)

Origins

"Shinrin-yoku," or forest bathing, began in Japan in the early 1980s as a public health initiative. Recognizing the rising stress, urban crowding, and long working hours, Japan’s government saw forest immersion as a low-cost wellness practice rooted in nature. By institutionalizing shinrin-yoku, Japan sought not only to enhance public health but also to mitigate burgeoning healthcare costs. With healthcare expenses consuming a significant share of national budgets, preventive measures such as forest bathing offer a holistic approach to maintaining societal well-being. Estimates suggest that the program saves billions of yen annually in stress-related healthcare costs, underscoring its economic impact and policy significance. (Effects of Shinrin-Yoku Retreat on Mental Health: a Pilot Study in Fukushima, Japan, 2024)

Institutional Research

The Japanese Society of Forest Medicine

The Center for Environment, Health, and Field Sciences at Chiba University

The Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute

These groups began measuring cortisol, HRV, immune markers, and mood in forest environments.

Where forest bathing stands today

It’s part of Japan’s preventive healthcare recommendations.

South Korea has developed “healing forests.”

Europe and North America now have certified nature-therapy guides.

Medical schools increasingly recognize the benefits of nature exposure.

Insurance companies in the US, however, do not cover “nature therapy sessions.”

Forest bathing has moved from “hippie concept” to “emerging field of environmental health.”

Ancient Aromatic Resin: A 3,000-Year-Old Clue

Let’s return briefly to Genesis 2:12, which mentions:

“gold, aromatic resin, and precious stones.”

The ancient Hebrew word “bdolah” (often translated “aromatic resin” or “bdellium”) refers to a fragrant tree exudate similar to myrrh.

Why this matters:

It shows ancient people prized tree resins as valuable commodities.

Resin hardens into “tears” packed with terpenes—cousins of modern phytoncides.

Frankincense and myrrh were traded like gold because their chemistry had:

·

Antimicrobial uses

Anti-inflammatory properties

Aromatic and ritual value

Medical applications in wound care, embalming, and incense (Incense trade route - Wikipedia, 2025)

In a sense, ancient resin trade routes were early explorations into the biological power of plant chemistry—a precursor to today’s forest-medicine research.

So Are Phytoncides the “Aromatic Resin of the Air”?

In a poetic yet scientifically grounded sense: yes.

Resin is the solid form.

Phytoncides are the airborne fraction of similar terpene families.

Warmth causes resin to vaporize—creating forest aroma.

Both share structural motifs that interact with human physiology.

The ancients valued the solid form. We’re discovering the vapor matters too.

Other Biblical references:

Everyone has probably heard of the value placed on “gold, frankincense, and myrrh"! They were, apparently, highly valued at the time of Christ’s birth since those were the gifts presented by the three wise men. Both frankincense and myrrh are derivatives of pine tree aromatic resins. It is unlikely that they were regarded as perfume alone. They no doubt had significant health and liturgical applications. Did you know that you can buy all three on Amazon?

The Ebers Papyrus from Egypt, 3,500 years ago (!!!), discussed the importance of frankincense and myrrh concerning their medicinal properties in wound care, pulmonary treatments, intestinal diseases, and mood improvement, among other topics. Phytoncides have been an important part of wellness for as long as people have been sniffing the scents of a natural forest.

Conclusion: The Old and the New Meet in the Forest

Forest air is a blend of ancient chemistry and modern biology:

Highly evolved plant defense molecules interact with the human immune pathway, confirmed by modern measurements and appreciated instinctively by humans across millennia.

Whether you’re breathing phytoncides on a mountain trail or reading about “aromatic resin” in a 3,000-year-old text, you’re witnessing the same phenomenon: humans noticing that trees change how we feel.

This is where history, chemistry, immunology, and everyday experience all point in the same direction.

As you prepare to step into your next forest adventure, envision the trail stretching before you, lined with towering trees whose crowns form a great green canopy. Feel the crunch of leaves beneath your feet and breathe in the invigorating scent carried by the gentle breeze. The songs of birds and the rustling of leaves provide a kind of music that echoes through the silence. This isn't just scenery. It's a living, breathing ecosystem calling out to be experienced. You might call it "forest pharmacy" for fun. We have called it "tree therapy" for 50 years, way before we heard about the Japanese version. Let the forest's life pulse through you and connect with this ancient chemistry designed to be part of our very being. To bring a touch of this experience into everyday life, consider a simple daily ritual: take five mindful breaths (oh, wait a minute, that sounds like the subject of a future video podcast!) beneath a neighborhood tree, letting the scents and sights remind you of the calm and vitality nature offers. For urban dwellers, city parks or tree-lined streets can offer a pocket of serenity. Engaging with these urban green spaces might offer similar benefits, helping to integrate nature's effects into your busy schedule. Be sure to read (or watch our YouTube video podcast) our previous episode on the health benefits of simply being in a “green” environment and how this alone can trigger subtle physiological changes. This small practice can help bridge the ancient connection with nature and incorporate its benefits into your daily routine.

Spoiler alert: In our next video podcast and blog, we will explore another very curious concern that is almost the opposite of this one, Microplastics! What are these doing inside my body?!

Thanks for reading. As with almost all our topics, we are not experts, just somewhat curious amateurs sharing what we have recently found out about something. Drop us a comment in the comments section or ask us about anything that resonates with you. How does forest hiking affect you? Let us know because we are curious about how this all sounds to you. Be curious with us. Watch our YouTube video podcast on this and other curious topics: YouTube.com/@somewhat-curious

You didn’t come this far to stop

You didn’t come this far to stop

Curiosity is a powerful driving force that often leads individuals to explore the unknown, ask questions, and seek out new experiences that enrich their understanding of the world around them.

Exploring the wonders of life together.

Connect

Learn

loveedavidmiller@gmail.com

123-456-7890

© 2025. All rights reserved.